Water is, without question, among the most prolific and useful substances on the planet. It covers 70 percent of the Earth’s surface and makes up 75 percent of our body weight. The “universal solvent,” it is vital to all forms of life. Despite its prevalence, or perhaps because of it, water is often forgotten or simply taken for granted.

[newsletter_signup_box]

It’s true also in beer brewing. Jamey Adams of Arches Brewing in Hapeville, Georgia, says that water comprises 90-95 percent of the actual beer we drink. Yet it is rarely discussed outside of the bowels of breweries and the feverish homebrew forums of the internet.

This may be because, despite its ubiquitous nature, water can be fairly complex. Plain water – pure, unadulterated H2O – rarely occurs naturally. Often water is littered with a medley of other compounds and microbes. This produces pH variances, alters reactivity and changes everything from color to taste.

So how do these immense variances occur and how does that affect the beer we drink?

(READ: Breweries Go Nuts Creating Nut Beers Beyond Peanut Butter)

Regional Beer Styles Tied to Water

Start with the history of beer development. Beer styles are often described in regional terms. There’s German-style lagers, Czech Pilsners, Irish stouts and Belgian-style beers. These are not the only beers to be found in these areas, but they tie back to style’s origin. They are usually stellar examples of that particular beer style.

Why does this happen? Why do the Irish make more stouts than the Germans? And why are the Germans known more for their lagers than the Irish? It is not like the brewers of these countries were unaware of other possible beer styles. So how did this dynamic develop? The water is the key.

John Palmer shows that assessments of Czech Republic beers found water that was low in mineral content – soft water. This water works best for producing beers such as lagers and pilsners. Ireland, with its mineral-laden hard water, found itself divining delectable stouts the likes of which could scarcely be produced anywhere outside the Emerald Isle. There are many examples of this, but the point is clear. Water is a really big deal, big enough to shape the history of beer.

So, why do these differences produce different beer flavors? It’s a matter of chemistry.

(READ: Winning a Medal at the Great American Beer Festival is All About Style)

Chemistry of Water in Beer Brewing

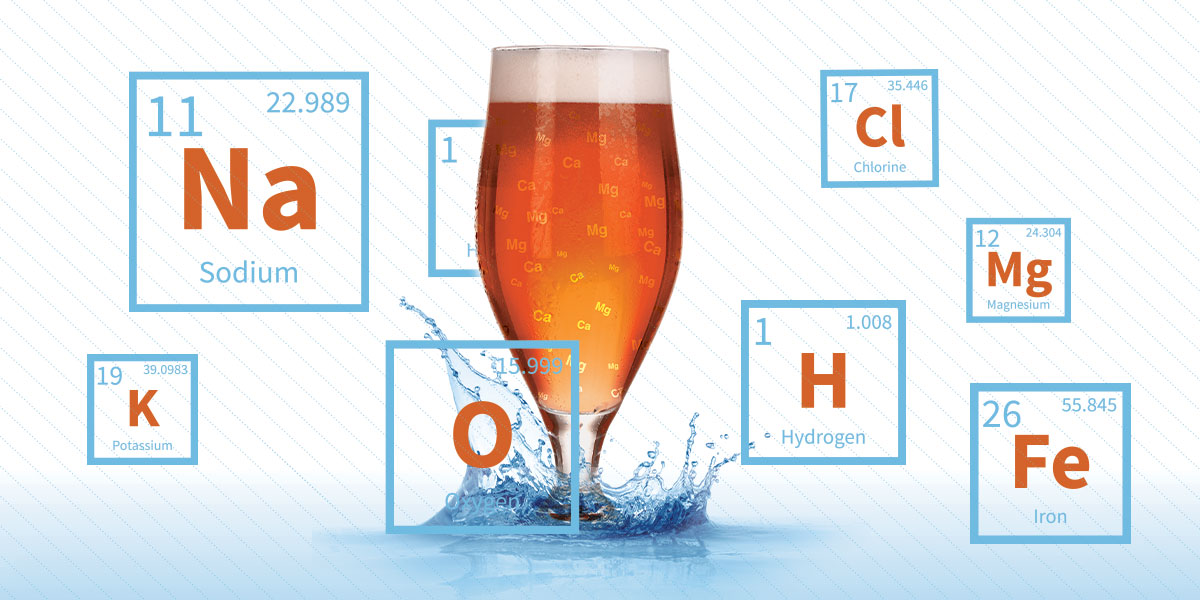

First, look at the kinds of things found in water that might contribute to beers flavors. In his book, “The Complete Joy of Homebrewing,” Charlie Papazian says the most crucial players are calcium, magnesium, sulfates, sodium, chloride and bicarbonate. That is quite a list, but this doesn’t even begin to cover all the components that you might find in water. There can also be trace amounts of microbes, fluoride, zinc and other compounds.

In “Water: A Comprehensive Guide for Brewers“, John Palmer and Colin Kaminski state that among these elements and compounds, calcium is king. This mineral is responsible for helping with yeast flocculation and facilitating the mash process. Calcium reacts with phosphates in malted barley to lower the pH in a process known as buffering. This helps enhance the activity of crucial enzymes such as alpha-amylase as they go about extracting and breaking up sugars as a part of the mashing process.

(INSTAGRAMMERS: Show Us Your Photos of the Independent Craft Brewer Seal)

Bicarbonate, on the other hand, is a compound that serves the opposite purpose. It raises the pH (i.e. increasing alkalinity). It’s used in the brewing process as a kind of counter-balance, preventing things from becoming too acidic.

Magnesium is, in a way, the least essential. It’s needed only in small amounts, and those amounts are typically found in the grains used for the beer anyway. However, magnesium is still an important player in the mashing process.

The remaining elements and compounds are known as the “flavor ions.” They directly affect flavor of the beer, each in its own way. Sulfates accentuate hop characteristics, most notably bitterness. Chloride enhances the body and the maltiness of the beer. Sodium imparts its own flavors that are usually desirable in specific beer styles like the gose.

Finding a Perfect Balance

It’s worth noting the “Goldilocks principle” can come into play here. While all of these substances can enhance beer in desirable ways, you can quickly have too much of a good thing. High levels of sulfates will make the hop flavor astringent and distasteful, while chloride in mass quantity will give the beer a medicinal off-flavor.

All of these chemicals are measured and recorded in parts per million (ppm). Their concentrations are unique to nearly every community in the U.S. like a kind of hydraulic fingerprint. A community’s water quality report is usually available online (and if you live in Pennsylvania (like me) you can access your local communities water chemical assessment here.)

(LEARN: Discover 75+ Beer Styles)

Tinkering with Local Water Chemistry

All of this information leads to another question. If the water of a community is set, and certain beers work well with certain chemistries, how do brewers brew a wide range of styles rather than only brewing the beers that their local water sources allow? They do something that humans are extremely good at doing: tinkering.

Brewers use chemistry to change the composition of the water before using it. Additives such as gypsum, baking soda and just plain table salt will give you copious amounts of the crucial compounds. That is why full-scale breweries and homebrewers alike can use them.

To those alcoholic alchemists brewing at home, many experts like John Palmer, Colin Kaminski and Brad Primozic who is the head brewer at Insurrection Ale Works in Heidelberg, Pennsylvania, advise that the most important aspect of water for the homebrewer to focus on is the pH.

“You know that distinct ‘homebrew taste’ that homebrewed beer sometimes has? When you taste that, you know that pH was a bit off,” Brad says.

He says the ideal pH is between 5.2 and 5.5.

“At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what you put in the beer if your foundation is wrong.” Brad Primozic, Insurrection Ale Works

Going With the Flow

As intriguing as playing with water chemistries sounds, mother nature can also dabble with water chemistries herself. This can present a constant headache for brewers. Brad studied chemistry when he was in college and still uses that foundation to this day at Insurrection. He says that when the snow melts or when there’s been days of considerable rain, he has to watch the changes to the water table constantly.

(VISIT: Find a U.S. Brewery)

“At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what you put in the beer if your foundation is wrong,” Brad says.

It is this laser-like attention to detail that truly makes some small breweries stand out.

From the broadest of aspects like the pH, to the smallest of details like the zinc concentration for yeast nutrition, water works as a complex but essential balancing act that every good brewer must perform. It may not always be straightforward and it may not always be easy, but it is fundamental to building an excellent beer.

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.

Share Post