The idea of beer trading is nothing new. People have been meeting in their basements to exchange and share exotic bottles since the beginning of beer. But the explosion of craft beer and the presence of the internet have developed a secondary market in America like we’ve never seen before. Some are exchanged as part of an even trade; others are purchased for more — way more — than they were originally sold. According to brewers and industry professionals, the secondary craft beer market has branched off in different paths, each being met with various degrees of favorability.

Beer Trading and Brewery Street Cred

At its core, the basic, honest concept of consumer-to-consumer beer trading has the potential to make the world go round, allowing beer drinkers to connect with other beer drinkers in different regions and swap local brews. For example, I live in Hawaii, and most are only available here in the islands. Given my remoteness, I also have very limited access to beer made off-island. For me to trade beers on a dollar-for-dollar basis (represented as “$4$” in the online trading communities) with someone in, say, Minnesota, could be a cool thing.

“Beer trading has opened up accessibility to beers from all around the world,” says Tim Golden, co-owner of Village Bottle Shop & Tasting Room in Honolulu. “It’s a great thing. If you want something that you can’t get where you are, you can trade with someone for it.”

For the individuals involved, swapping beers can be a great process. But what about for the brewery? Jayson Pizarro, co-owner of Hawaii’s newest and smallest craft brewery, Inu Island Ales, loves the concept of beer trading, from even swaps to secondary market sales.

(READ: Solera Brewing: American Brewers Explore an Old World Brewing Style)

“[The beer trading community] is a great thing for breweries,” Pizarro says.

Pizarro opened Inu Island Ales this past November, and he sees the secondary market not only as a way to build value for his brewery, but for his customers and local market. Currently, one of his beers, Chikara Mizu, is selling for about $150 online when it retails for $15. For the brewery, he said it has led to collaborations that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. As for his customers, the brewery is providing the local community with “currency” to go out there and land some of the top beers on the secondary market.

“[The secondary market] is a small part of the community [at-large] but huge in terms of your value and equity within the community,” Pizarro says.

Extreme Price Inflation

While beer trading can give newer breweries street cred, not all independent brewers share Pizarro’s enthusiasm and the secondary value of beers is at the heart of it. For example, let’s say Beer A costs $12.99 for a four pack when you buy it from the store. But because it’s made and released in limited quantities, people who obtain Beer A factor the demand for it into the resale value. Thus, once supplies at stores or the brewery have been exhausted, the online price for single bottles of Beer A skyrocket to $20 per bottle — or more.

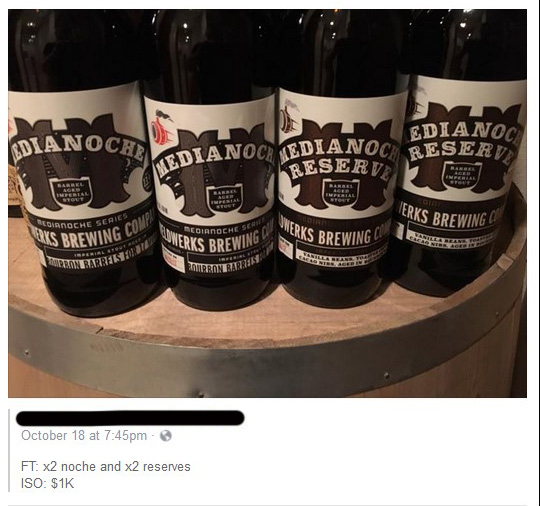

Here’s an extreme example: In 2017, we saw a seller on a Denver beer trading board ask $1000 for a collection of two bottles of WeldWerks Brewing Company’s Medianoche bourbon barrel aged imperial stout and two bottles of Medianoche Reserve (left), a price well over retail.

Neil Fisher, co-owner and head brewer at WeldWerks Brewing Co., thinks the secondary market is negatively altering the attitude of craft beer drinkers.

“We firmly believe that we make beer for enjoyment, and we do not make commodities,” Fisher says. “So while it’s fun to hear that our beers get shipped all across the country for people to try, it’s not as exciting when we hear that someone sold one of our bottles for $200-$300. It also seems like the secondary market is having a negative effect on the culture of craft beer, resulting in more entitlement and less fun. And at the end of the day, craft beer is supposed to be fun.”

Demand drives a market and inflated resale value is understandable to a point (the extreme Medianoche example is still outlandish). But individual beer buyers inflating the resale value has other consequences on the industry as a whole.

(READ: The Great Debate: Aging Beer Vertically or Horizontally)

In online communities such as Beer Advocate, members share various stories of bottles shops that pull popular beers off the shelves and up the price. In one example, a man visited a store that was originally asking $6 per bottle but had upped the price to $20 a bottle when it “realized how sought-after it was.”

From the bottle shop’s perspective, this was the going rate, since it was being resold online for that amount. Golden says that even though the market driving up the price is the nuts and bolts of capitalism, he’s not a fan of it in the long run.

“[Our bottle shop] could make more money on [rare beers] but we have the belief that if you’re fair and honest in the long run, customers will appreciate that and be loyal,” Golden says. “A great example was … a popular beer that only gets released once a year. It’s limited. Normal retail price is around $9-$11. Some places this year were selling it for $30 just because they knew people would pay it. To me, you don’t build long-term relationships with customers by screwing them any chance you can.”

Secondary Market and Unreasonable Expectations

Dan Becker of The Full Pint says the secondary market has other pitfalls. In his opinion, paying above retail price for a beer skews the perception of that beer, and the secondary market creates a false perception and unfair evaluation of individual beers.

Consider a scenario where you have purchased a beer on the secondary market for well above its retail price — let’s say you spent $100 on a beer that a brewery originally sold for $15 per bottle. But you’re pumped about it. You’ve been reading a lot about this popular beer online, and you’ve negotiated for several days to find someone willing to sell it at that price. Becker says that when you receive that beer, your expectations are going to be higher than they normally would, considering you’ve read so much about it and spent time and money obtaining it. This will lead you to love it or hate it, Becker says, which he finds unfair.

(READ: How I’m Approaching Craft Beer in 2018)

Alternatively, your high expectations might lead to a negative view of the beer, where the taste doesn’t back up the hype, time, and money you’ve invested. In this way, Becker thinks breweries can both benefit and be harmed by the skewed perceptions of secondary-market participants.

“The brewer is being honest — there’s a $15 bottle of beer,” Becker says. “It’s the people who pay more that come into it with different expectations, and that’s unfair.”

Beer Trading and the Quality Conundrum

Then there are concerns about the freshness and quality of the beer. Once it leaves the bottle shop or brewery, second-hand traders have no idea how the beer has been stored and treated.

“If you trade for a bottle of beer that just spent four days in transit, you need to understand that is not even close to the same beer you would get at the brewery.” Natalie Cilurzo, Russian River Brewing Co.

“For us, it comes down to quality,” says Natalie Cilurzo, co-owner and president of Russian River Brewing Company. “We don’t want our beers ending up unrefrigerated on the back of a FedEx truck in the Arizona desert, or sitting in a warehouse for days on end. Beers like Pliny the Elder are extremely perishable. By the time it reaches you, it will not be in the best condition. If you trade for a bottle of beer that just spent four days in transit, you need to understand that is not even close to the same beer you would get at the brewery.”

Concept Behind ‘Winning’ Beer Trades

Becker says there’s also another growing trend that has put a damper on beer trading: the concept that trades have to be “won.” Whereas the utopian version of beer trading begins and ends with retail-oriented dollar-for-dollar swaps, some modern-day traders now operate on the secondary market’s evaluation of the beer and set out to “win trades” instead of simply trading beers. Like players on a sports team or baseball cards, each individual beer’s evaluation is a matter of opinion.

“You may have to trade two to three beers to get that one beer that is more expensive or harder to get,” Golden explains. “At the end of the day, if you really want something, you’ll be willing to give a little more to get it. It’s no different than when we were kids trading baseball cards. If you wanted that Ken Griffey Jr. rookie card, you needed to trade something of equal or greater value to get it.”

(VISIT: Find a U.S. Brewery)

Beer Hoarders and the Pursuit of Whales

It’s one thing to buy two bottles of a rare beer and swap with a friend. It’s another to buy up dozens of bottles — hoard the beer — with the sole intention of reselling it all for a profit. Breweries and beer stores try to prevent this behavior by imposing limits on the number of bottles that can be bought per person, yet these limits are easily circumnavigated. The classic example is beer hoarders who ask their friends to purchase beer on their behalf, allowing them to get around per-person limits and accumulate a lot of beer.

Despite growing concerns and examples of beer hoarding within the trading communities, Golden says he’s not overly concerned about it in the long run. For one, it’s a small percentage of people who hoard, and there’s still plenty of room for even trading out there. The inflated secondary market may make it difficult and/or expensive to acquire “whales” — the name for rare, highly sought-after beers — but Golden feels there’s more than enough to go around.

“If you only hunt whales, then you’re missing out on a lot of great beer from great breweries,” he says.

Though there may be a tendency for people to be annoyed by the darker aspects of the beer trading community, Golden says that, in his opinion, it’s good for craft beer.

“At the end of the day, if people are passionate and excited about beer, it’s good for everyone — breweries, retailers, bars, and distributors,” Golden said. “When people stop caring about beer, then we’re in trouble.”

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.

Share Post